A classic video technique

Sep 30, 2025

In this post, I suggest a simple tweak to a familiar video technique – one that shifts the focus from controlled grammar practice to a real-life task.

Back to the screen

Many years ago, when I did my Cert-TESOL course in Barcelona, we had a session on teaching with video. The technique I remember best is one you might be familiar with.

It involves putting students into AB pairs: A students can see the screen, B students cannot. This creates an information gap, requiring the A students to describe the video to the B students. Afterwards, the roles are reversed.

The task, which requires speakers to provide a real-time running commentary, is best suited to video clips that show a clear sequence of actions or events.

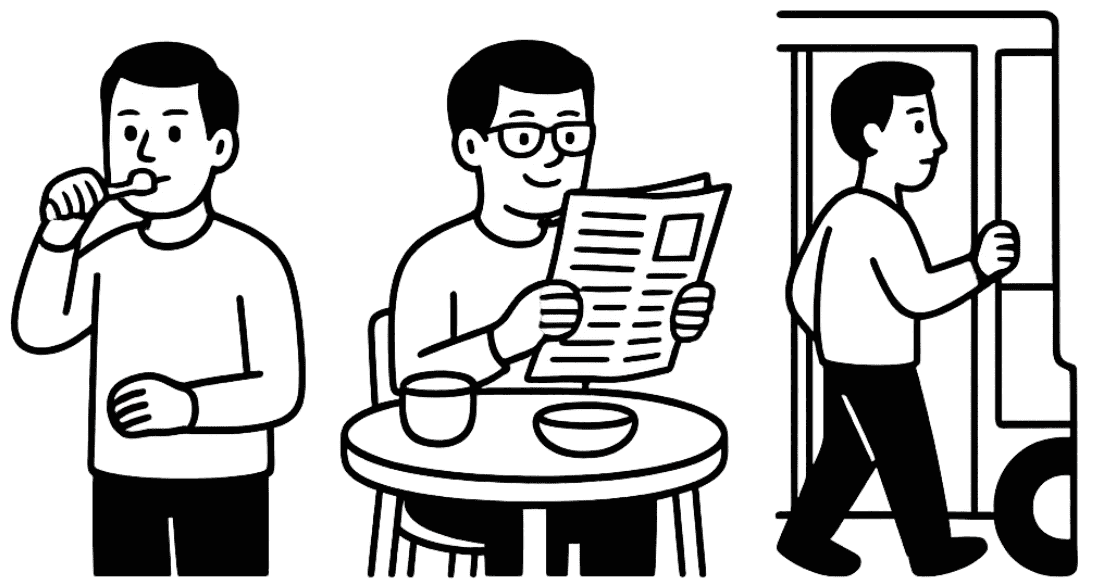

The video used in our training session was made specifically for language learners. It showed a man going through his daily routine – brushing his teeth, having breakfast, going to work, and so on.

It was all part of a PPP (Presentation – Practice – Production) framework to grammar teaching, the grammar point in question being the present continuous:

- He’s brushing his teeth.

- Now he’s having breakfast and reading the paper.

- He’s getting on the bus.

A critique

The back-to-the screen video technique most likely dates back to the 1980s – a golden decade for video in language teaching – when a number of publications introduced teachers to the concept of ‘active viewing’.

In some respects, it must have been a breath of fresh air. And the fact that I remember it all these years later (23 years later, to be exact) suggests that I enjoyed it.

But in 2025, I have doubts about its usefulness, especially when it is presented as a generic video technique. The problem with the technique is that it only works for very specific types of video content. In the hundreds of clips I have used in my teaching and training, I could only identify one or two that would be suitable.

Today, video is short and bitesized. Consider the following viral clip of a baby having her very first taste of ice cream. It lasts only 35 seconds. Could we create a back-to-the-screen activity with a video like this? If so, what would we do differently?

Spot the difference

With one small tweak to the format described above, we can create a video task that is more adaptable and versatile – and one that lends itself to a real-life communicative function.

Here is a different approach. Can you spot the difference? Most importantly, what is the real-life communicative function that I'm speaking about?

- Put students into AB pairs.

- Ask them to sit so that A students can see the screen, and B students cannot.

- Play a short video or video excerpt – with the sound up. The ice cream baby video would be perfect for this.

- A students watch in silence; B students listen and try to work out what is happening.

- Afterwards, B students ask A students closed questions to speculate about what's going on in the video.

- Finally, A students put the video narrative into words – from beginning to end.

Discussion

There are a few things to say here. You might have noticed, for example, the listeners' more active role.

But the key difference is this: instead of providing a running commentary, speakers wait until the end of the video. Then they process what they saw and put the narrative into words.

The real-life communicative function that I mentioned is storytelling.

Video for storytelling

For language teachers and learners, there are three clear advantages to using storytelling instead of running commentary:

1. A real-life task

'Telling' videos is an everyday human act. Imagine telling a friend about a funny TV advert, a piece of shocking news footage or a scene from your favourite film.

Telling videos is also the most communicative way to approach them. It can be applied to all sorts of content – including TikToks and Instagram Reels which offer bitesized narratives, perfect for putting into words.

2. The quintessential 21st century skill

In a world of endless scrolling, short attention spans and competing voices, the ability to tell a story has never been more important. And when students do so, they practise more than just language and grammar.

Learning storytelling means learning to hold attention, make meaning and share experiences that others can relate to. Storytelling belongs at the centre of language learning.

Telling videos allows students and teachers to build these skills with confidence – and without the need to go personal.

3. Visual literacy skills

Like storytelling in general, telling a video requires planning and preparation. But putting a video narrative into words requires the extra step of mindful viewing and thinking about what we see on the screen. This is a powerful entry point for developing visual literacy skills.

LessonStream Video Course

If you like the idea of using video as springboard for developing storytelling, this is the perfect course for you.

The courses consists of two components:

- Taking Video Apart: master multimodality, spark curiosity, get students talking

- Videotelling: a story-based approach to video

Sign up to the LessonStream Post and get fresh ideas for teaching with video, image and story – straight to your inbox. I'll also send you my ebook – Seven Ways to Curiosify Your Students